Given here are the following two chapters from the Grammar:

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

12.1 The notion of minimal constituents

Our first task is to identify the minimal constituents, the building blocks of analysis (see above, 3.10).

The constitutive nature of the constituents must be understood as -emic (see above, 2.1). We must define those constituents which are mutually exclusive and which together form a closed system. To this end, I will first identify, in this chapter, the broadest classes of constituents, and will then, in the next chapter, define the types of constituents which belong to each of the classes.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

12.2 Constituents proper and para-constituents

Within a grammatical frame of reference, the constituents proper must be minimal and systemic (see above, 3.10). The system within which they are inscribed is the record – physical and descriptive. They pertain to the things found in the ground and to the parameters that are overlaid on the physical reality. I will deal with the details in the following paragraphs.

Besides constituents proper, I recognize another class which is in some ways parallel (para-constituents), which I call incidentals. An incidental is a non-systemic item of description, i. e., an entry in the recording system that refers to situations and events pertaining to chronicle details – e.g., strategy to be pursued on a given day, daily review of entire unit, weather as observed by a given supervisor, surveying as pertaining to given operation, etc. By definition, this class is properly outside the system, and thus it is not in fact a constituent as such. It is considered alongside the constituents proper because it occupies in the archive an analogous rank, and may accordingly be called a para-constituent.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

12.3 Classes of constituents proper

There are two classes of constituents proper, which I call elements/para-elements and referents.

An element is a minimal stratigraphic/typological constituent of the data, which is further defined as either stationary (features – e.g. wall, floor), or movable (items and lots – e.g. blade, sherd lot).

A para-element (on the analogy of terms like para-medical, para-normal, or even paraphrase) is an element which does not exist as such (stratigraphically), but is presupposed on the basis of direct evidence (generally an impression left on other elements: a peg’s impression on a sealing), or indirect evidence (generally an argument, e.g. a wall assumed on the basis of a building’s layout). In other words, the term refers to elements which exist only inferentially, but are nevertheless assumed to be real (on the basis, precisely, of a reasonable inference) and are not just imagined. By nature, a para-element is identical to an element, and belongs in the same class. It is only in terms of their evidentiary grounding that elements and para-elements should be distinguished.

A referent is a minimal constituent of the recording system, pertaining to either the physical network (e.g. control point, relay), or the analytical network (e.g. journal, photograph).

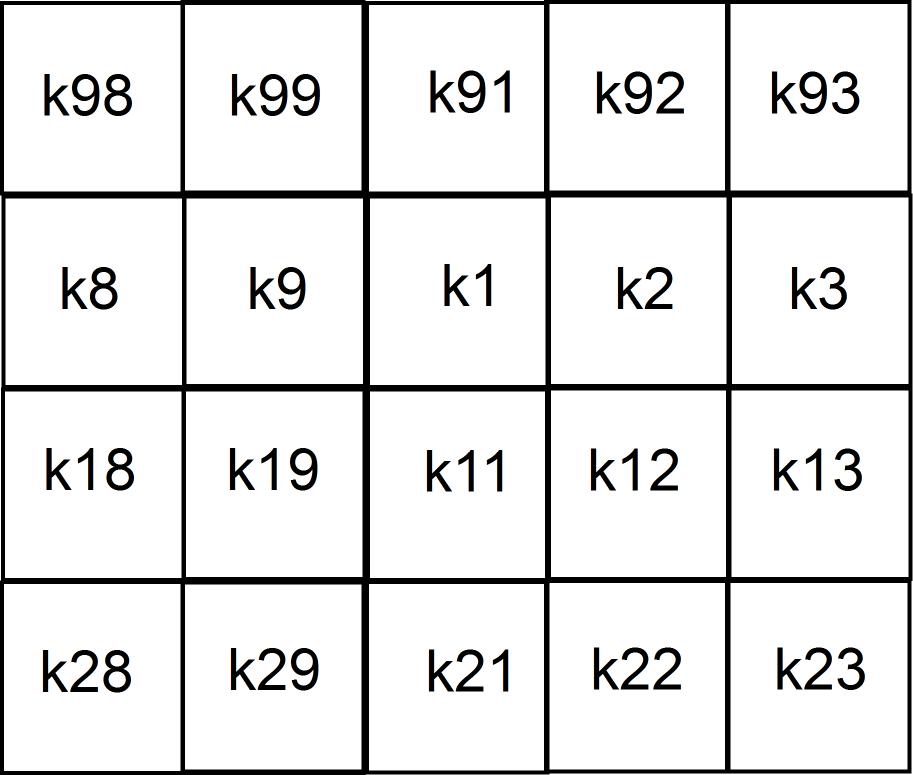

Following is a chart that surveys synoptically the

criteria for distinguishing the main classes of constituents and incidentals.

|

constituents |

element |

minimal stratigraphic/ typological constituent of data |

stationary |

feature |

|

movable |

object, specimen, sample |

|||

|

para-element |

an element which does not exist as such (stratigraphically), but is presupposed on the basis of |

direct evidence |

such as an impression left on another element, e.g. a peg on a sealing |

|

|

indirect evidence |

generally an argument, e.g., a wall assumed on the basis of a building’s layout |

|||

|

referent |

minimal constituent of recording system, pertaining to |

physical network |

e.g., control point, relay |

|

|

analytical network |

e.g., journal, photograph |

|||

|

para- constituents |

incidental |

non-systemic unit of description, i. e., situations and events pertaining to chronicle details identified by appropriate specific label ِ e.g. sg (strategy to be pursued on a given day), dy (daily review of entire unit), we (weather as observed by given unit supervisor), sy (surveying as pertaining to given unit), etc.

|

||

Fig. 12-1. Constituents and para-constituents.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

12.4 Minimality and systemics

The constituents are minimal in a relative sense. This means especially two things. First, each class excludes any other – in this respect, they are minimal because no constituent so defined can be subsumed under another (an element such as a wall cannot be subsumed under a referent such as a locus). Second, within each type of constituent, nesting of subtypes is possible – in this respect they are minimal without excluding the possibility of combinatorial processes (an element such as a wall may consist of components such a brick).

The notion of system underlies the classification, meaning that any constituent is to be understood in relationship to all other constituents, and not anectodatlly, in and by itself. In the next chapter we will look specifically at the specific types of constituents and para-constituents, i.e., the concrete embodiments that elements, referents and incidentals can take. First, however, we should describe the structure and organization of the constituents within the system, i.e., their intrinsic and and their combinatorial properties.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

12.5 Intrinsic properties as criteria for definition

There is a rich set of properties which defines any given constituent. The specifics of these properties are given as paradigms of variables or attributes, which I call rosters, and as lists of variants or attribute states, which I call lexica; they are described in detail below in Section II/B. Here I will explain the concepts.

Property is one of several analytical traits which together define a constituent. It is to be further differentiated into variables (or attributes) and variants (or attribute states – see already above, 3.8).

A variable or attribute or attribute argument is one of a set of possible qualities or identifying marks which may be found to characterize a given constituent (e.g., type of contact or color). Since these variables are listed as part of a roster, they are also called “roster slots.”

A variant or attribute state is the content of a variable, i.e., the particular quality which happens to fill the particular slot (e.g., white). Since these slots are those listed within a roster, the variants, which fill these slots, are also called “roster contents.”

Variables and variants are organized according to the logical structure of any given whole (e.g., emplacement), resulting in specific paradigms. These are essentially inventories of choices sorted in a structural sequence. There are two types of pertinent paradigms; a roster is a structural sequence of attribute slots (variables), and a lexicon a list of attribute states (variants for variables).

A special category that is related to the lexicon is that of standards. These are criteria that define variants according to precise parameters, e.g., the Munsell standard 10R 5/3 “weak red” as a more specific and verifiable definition than a more generic “reddish.”

Any given constituent is defined on the basis of a batch of properties that are drawn from the paradigms indicated, and it is identified through a unique label. A label is an alpha-numeric code that is derived from a sequential log. There are different labels that correspond to different degrees of specificity.

Every constituent must have a generic label, which is based on stratigraphy and on a minimum of typological specificity – essentially features and items.

To the extent that typological analysis proceeds, higher levels of specificity are possible, and they are reflected in a variety of specific labels.

This overall classification is presented synoptically in Fig. 12-2.

|

attribute |

one of several analytical traits which together define a constituent |

variable |

or Roster Slot or Attribute Argument: category of element structure (e.g., color) |

|

|

variant |

or Roster Entry or Attribute State: content of variable (= typological or specific label, e.g., white) |

|||

|

paradigm |

inventory of choices sorted in structural sequence |

roster |

structural sequence of attribute arguments (variables) |

|

|

lexicon |

list of attribute states (variants for variables) |

|||

|

standard |

description of parameters defining variants |

implicit (e.g., “brown” as common sense value) |

||

|

explicit (e.g., Munsell color value) |

||||

|

label |

alpha-numeric code derived from sequential log, which identifies uniquely any given constituent |

generic label |

minimum stratigraphic/typological definition (e.g., feature, item) – primary or first level of specificity |

|

|

specific label |

intermediate typological definition (from lexicon of variants, e.g., wall, tablet) |

|||

Fig. 12-2. Intrinsic properties of consituents.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

12.6 Combinatorial properties of elements

The structure of an element can be defined on the

basis of its combinatorial properties, which result in either splitting or

joining. On the one hand, an element may be split or subdivided into

components, and on the other, several elements may be joined or grouped into

clusters, as summarized in the following chart.

|

splitting |

component |

typological subdivision of element (e.g., brick, sherd) |

|

sub-component |

quantitative subdivision of element (e.g., sherd-1, sherd-2) |

|

|

joining |

cluster or complex constituent |

grouping of elements or referents according to given criteria (e.g., aggregate) |

Fig. 12-3. Combinatorial processes.

A component is a typological sub-unit of

an element, and sub-component a quantitative sub-unit of either an

element or a component (referents do not have components). There may be one or

more component of either type for any given element. For example, if the

element is a jar, a typological component of the jar may be a seal impression

on its shoulder, and a second typological component may be a cloth impression.

If there is more than one seal or cloth impressions, there will be more than

one quantitative sub-unit of that particular typological component. Analogously,

for a pottery lot, there will be one or more sherds (quantitative sub-component)

for any given type of ware and/or shape (typological component). This is

represented synoptically in the following chart.

|

element |

typological component |

quantitative sub-component |

|

jar |

seal impression |

1 |

|

cloth impression |

3 |

|

|

pottery lot |

simple ware |

35 |

|

early Trans-Caucasian |

1 |

|

|

metallic ware |

3 |

Fig. 12-3. Components and sub-components.

A cluster is a grouping of elements or referents according to a given criterion. For example, a group of vessels functionally related and sitting on the same floor constitutes a cluster (aggregate), and so is a group of photographs related through a set of views (web). A cluster may be viewed as a complex element. The most important of these clusters fall under the category of aggregates.

The difference between elements and clusters is in the degree of nesting established, or choice of parameters made, by the excavator: for instance, bricks are generally considered as components of wall, and a wall as an element of an aggregate. Paradoxically, it may be said that a site (or the world itself!) is an aggregate, but neither susceptible of proper analysis. On the other hand, a wall is an appropriate unit of analysis if considered an element. As was already stressed above (10.1), there is no element which is so in an absolute sense; it is only a relative function of nesting choices.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

12.7 Summary

The analysis given above for constituents and para-constituents (incidentals) is summarized in the diagram given below as Fig. 12-5. The constituent is represented by the main box, next to which one may place the incidental, which is outside the main system, and does not therefore have any of the systemic articulation of the constituent, but fills an analogous location within the archive.

Within the main box, the constituent proper is the central node. The two main classes are shown as branching out below this central node.

The structure is represented in two ways – the components splitting the element as lower branches (for typology and quantity, in sequence; the quantitative component ia also called a sub-component), and the clusters serving as higher nodes which group one or more individual constituents.

The properties or attributes are represented by the

variables or attributes (as listed in the rosters), for each of which there is

in turn a variant or attribute state (as listed in the lexicon).

|

Fig

Fig. 12-5. Summary

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

Constituent Inventory

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

13. Introductory

Within the two broad classes of constituents identified as elements and referents, we must now describe the specific minimal constituents that can be identified in the archaeological record. The applicable inventory is given in this chapter, with an explanation of the underlying concepts. The pertinent codes will be introduced in the next chapter.

In the presentation, I will further distinguish between two sets of terms.

The first set includes those elements and referents that can be so understood in a technical as well as a conceptual sense. They are also subject to labeling, in the sense that they are identified by specific alphabetic codes and are indexed numerically (see next chapter).

As such, they are used as organizing principles in the archive.

The terms of the second set, on the other hand, are only used discursively for descriptive lexical purposes, and thus receive no label.

It is important to note that only indexed constituents (those which receive a label) are properly part of the closed -emic system (for which see above, 3.4): none can be added, nor can any be subtracted, without affecting the system as a whole. Purely lexical (non-indexed) constituents, on the other hand, are part of an open system: those mentioned here are only indicative, and as many can be introduced as is useful in any given context.

In this chapter, indexed constituents are given in bold italics, and non-indexed ones are given in regular italics. One will also find a convenient synopsis in fig. 13-1.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

13. Elements

There are two major types of elements, depending on whether they are stationary or movable. The distinction between the two does not rest on the physical impossibility or possibility, respectively, of moving what is found in the ground. A bridge or the Assuan temples were moved, the pyramids could be moved, but they remain nevertheless stationary. The proper discrimination between the two types should rather be understood in the following terms. A stationary element is one whose typological identity is tied to a place, whereas a movable element is one whose typological identity is independent of place. Thus a wall or a floor accumulation are such to the extent that they remain in place as originally found: a dismantled wall, a sifted floor accumulation are no longer a wall or a floor accumulation. By contrast, a jar or a chunk of wood remain such regardless of whether they are seen in their original context or not. Note that the link to a place is not meant in a geo- or topographical sense: the London bridge moved to Arizona or the Assuan temples raised to higher ground retain their typological identity as stationary element (whatever else may have been lost in the process). Rather, the link to a place is meant in the generic sense of emplacement (see above, 2.2; 4.2): it is not only the permanent correlation of bricks and mortar that make up the wall, but also its permanent correlation to other walls, floors, etc., that gives it its proper identity as a wall. (In this sense, topography and geography are higher nodes which give further meaning to the wider assemblages of walls and floors – and this is what is lost in the case of the two examples mentioned above. But the stationary integrity of the elements can be reconstituted at the lower nodes of a given structural entity – a bridge, a building.)

The distinction between stationary and movable elements is essentially stratigraphic, since reference to typology is closely related to emplacement. I prefer to retain such a minimalist distinction, rather than introducing more differentiated definitions, for two reasons. First, the more generic the definition the less problematic is a decision in the field at the moment of excavation; there is ample space for greater specificity within the sphere of lexical definition that can be added at any time during subsequent analysis. Second, it is preferable to remain as close as possible to stratigraphy as distinct from typology in the primary labeling, since the former is the primary goal of the excavation process as such. For this reason, I do not distinguish further the stationary elements into such categories as installations and deposits (see Schiffer; Miller-Rosen; Pfälzner).

The term used for any stationary element is feature. Under this term are subsumed, therefore, such diverse entities as a wall or a pit, a floor surface or a floor accumulation.

The term used for any movable element is item. Under this term are subsumed, therefore such diverse entities as a cuneiform tablet or a jar, a carbon sample or a stone specimen.

Items are subdivided in two categories, depending on the method used for their volumetric localization. An item proper is triangulated individually (see below 16), while a q-lot (for quantity lot) is a quantity of movable items (further specifiable as components), triangulated as a volume. A q-lot has the following characteristics: it is defined (1) as a locus (see presently) and (2) as a level (intersecting the locus; see presently for the notion of level); also, (3) it is valid for only one day of operation.

It is important to stress that items proper and q-lots are distinguished purely in terms of volumetric specification (see presently for the relationship of q-lots to aggregates). As indicated, an item is triangulated individually, whereas items in a q-lot (q-items) are triangulated with reference to a larger volume. A q-lot may thus be conceived as a parallelepipedon (more simply, a box) containing a variety of items which are triangulated not individually, but by reference to the larger “box.” It appears, then, that a q-lot must be further distinguished to refer to individual items within it. Accordingly, the items within a q-lot are differentiated into three categories, which reflect the relative frequency of what can be found within a q-lot: pottery; bones; anything else (objects, specimens or samples).

To summarize, movable items fall into the following groups:

item proper (triangulated individually)

items within q-lot, triangulated

within a “box” and distinguished as:

pottery

bones

any other items

The following lexical definitions of elements will also be useful for an understanding of the concept of item. An object is a manufactured item. A specimen is a non-manufactured item, subject to count (e.g. a single stone), whereas a sample is a non-manufactured item, non subject to count (e.g. soil). One should not confuse, therefore, “item” with “object,” “specimen” or “sample,” since “item” is primarily a stratigraphic concept, while the others are exclusively typological terms. In other words, an item can be an object, a specimen or a sample.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

13.3 Para-elements

A composite is a normalized rendering of an item of which multiple exemplars

exist. This definition could be applied to a variety of situations, e.g., the

extrapolation of surface lines in drawing a vessel or wall surface, is a

normalized rendering. However, the term is restricted to only such situations

defined as pertaining to “items for which multiple exemplars exist”; the term

itself, “composite,” refers to such multiplicity rather than to the normalization

which occurs. A composite is assumed as a concrete single element, not as an

idealized category. Examples are a composite brick (rendered from fragments) or

a seal impression (rendered from a multiplicity of individual rollings).

Note that the concept of composite does not apply to the combination of different drawings that are joined together, as, for example, in the case of profiles from different loci that are linked into a single drawing.

A negative is a missing item, and a trace is a missing feature, present as void and documented by the physical imprint it has left of part at least of its surface(s) on other element(s). Sample negatives are objects on which sealings were placed, seals from which rollings were rolled, shovel marks; sample traces are quarried walls that have left a void filled with later detritus. The two terms “negative” and “trace” are used so as to have the benefit of different labels for items and features, respectively; they otherwise refer to the exact same concept. Either term refers to the mirror image of the original element (e.g., the impression of a basket on the back of a clay sealing): in this sense the negative or trace is the interface between the original element and the void which has taken its place. However, the terms “negative” and “trace” refer not to this mirror image in a photographic sense, but rather to an element that is documented but not currently existent (thus a seal documented by a seal impression).

The following lexical definitions may help explain further the concept. A mold is the physical embodiment of the outer face of the void (the envelope around the outer part of the interface). A cast filling the void would give an accurate representation of the missing element (and would be a positive in a photographic sense).

To sum up:

|

negative/trace |

original element, present only as void |

|

imprint |

interface left by negative/trace, now outer face of void |

|

mold |

physical embodiment of imprint, or physical envelope of interface (interface as seen from outside) |

|

cast |

filling of void contained by interface, or copy of original negative/trace (interface as seen from inside) |

Zero is a missing feature, which is inferentially probable but has left no physical trace. The term “zero” is used to stress the fact that no direct physical evidence is left of the element. Only zero elements which are essential for discussion will be postulated (for instance, a totally eroded fourth wall of a room), since there is otherwise no end to the number of zero elements that could be posited (e.g. door lintels, windows, etc.).

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

13.4 Complex elements

An aggregate is a cluster of elements, defined on the basis of depositional analysis, e.g., items on a floor. It is to be distinguished from an assemblage, which is a cluster of elements, defined on the basis of typological analysis, e.g., walls, spouted jars. An assemblage is considered a referent, since it is not found as such; see presently 13.6 (3).

A join is the combination of two or more items which are stratigraphically distinct (because they have been found in distinct emplacements), but fit together and thus can be shown to be components of the same item. Each of the discrete stratigraphic items retains its original designation (and labeling) as an individual item.

Note that a q-lot is a complex element as well, in a very specific sense: it comprises a variety of typologically distinct movable items. If I consider it, however, an element (see above, 13.2), it is because of the considerations about nesting for which see above (13.4). Accordingly, a q-lot receives a single element label, and is further subdivided into components, while the individual entities within an aggregate are given individual labels as elements, and are subsequently subsumed under the distinct label of the aggregate.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

13.5 Referents

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

(1) Volumetric localization or positioning of elements

A marker is a triangulation point set by the surveyor; it includes benchmarks (permanent markers) and control points (temporary markers used to measure relays, and generally removed during the course of excavation). Benchmarks are further differentiated into primary and secondary, depending on the degree of precision which distinguishes them: only primary benchmarks are obtained with full closure and may thus be considered to have first order precision; secondary benchmarks and control points, on the other hand, are obtained with second order precision.

A relay is a triangulation point obtained by the excavator, by measuring from markers. Occasionally, a relay label may also be given to triangulation points set by the surveyor, hence endowed with greater accuracy than a relay proper. Thus a secondary meaning of the category of relays refers to the listing of triangulation points included in the book of a given operation.

A projected relay is one that does not exist as a physical point in the ground, but is assumed for specific triangulation purposes.

Note that if the excavator can make use of a total station, the degree of precision of a relay may equal that of a benchmark. Even so, it is useful to retain the terminological distinction between markers and relays.

Two other lexical terms belong here. A section is a physical plane cut vertically through the deposition. A profile is the analytical rendering of a section (an index to spatial relationships of elements contained in the volume through which the section is cut).

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

(2) Analogical representation of elements

A view is a window on a constituent or a cluster of constituents (e.g., a wall, a tablet in situ, a structure, a marker), giving an analogical representation by means of photography. In practice, every view is embodied in one or more photographs; alternatively, the term “photograph” refers to the physical embodiment of the view. However, since a view abstracts from the photograph as such, the concept of view includes photographs produced with standard cameras, digital photographs, and scans of standard photographs. The main view is a single view in a web (see presently, 13.6 (2)), onto which secondary views are mapped as part of that view’s template (see presently, 13.6 (2)). A secondary view is a view within a web, for which no independent template is given, and which is instead mapped onto the template of the corresponding main view.

Given a fully three-dimensional photographic record, the application of the concepts of view and of web will be altered, but the basic underlying notion will remain the same. A view is the crystallization of a moment of understanding with the superimposition of labels that serve as an index to the analytical breakdown of the stratigraphic reality. Thus a thorough implementation of a GIS system will in effect serve as a maximal view, with direct hyperlinks to the same set of analytical details for which a grammatical definition like the one I am proposing here will continue to serve as an essential infrastructure.

A drawing is an analogical representation of measurements for a given constituent or cluster of constituents, by means of hand drafting. As with a view, the concept of drawing abstracts from its physical embodiment, and thus it subsumes hand drawings, digital drawings, and scans of hand drawings.

A sketch is the same as a drawing, but for temporary use only. Since it is not a permanent part of the archive, and it does not qualify for electronic storage, it is not labeled as referent. If, for whatever reason, a sketch needs to be integrated in the archive, then it is considered a drawing.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

13.6 Complex referents (referent clusters)

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

(1) Volumetric localization or positioning of elements

A locus is a volumetric unit with minimal and undefined horizontal axis and unlimited vertical axis. Its converse is the level, a volumetric unit with minimal vertical axis and unlimited horizontal axis. Since we rely fully on absolute coordinates (and thus absolute elevations) for individual elements, and since the concept of stratum is used to refer to temporal sorting (see presently), a level is not used as an indexed referent.

A sector is a subdivision of an

area or book. It is generally introduced for operational reasons, but indexed labeling

remains at the level of the area/book. This may happen, for instance, when two

distinct operations are conducted simultaneously within the same area, but

cannot easily be recorded on the same physical book, e.g., because of a great

difference in elevation or the presence of high baulks between the two sectors.

|

A square is volumetric unit with medium and fixed horizontal axis, and with unlimited vertical axis; it often includes smaller loci. |

|

A quadrant is a partition of a square, introduced for operational reasons to be specified individually. In order to be assigned a distinct label, a quadrant must be defined as a locus.

An operation is a generic term for a unit or an area, a square, or a sector.

A zone is a topographical portion of the site, without precise boundaries, and loosely identifiable for some recognizable traits, such as the nature of the contours or the presence of some distinctive feature (see below, fig. 14-…, for a list of labels used in Mozan.) It is indexed numerically for units, and alphabetically for areas.

A unit is a portion of a zone defined logistically for operational reasons and indexed numerically (e.g., A1). It serves as the basic sorting criterion for all field numbers assigned during the excavation. Given my understanding of the grid as a volumetric, rather than a physical, entity, units can be, and generally are, wholly asymmetrical, see below, 26….

An area is a portion of a zone, defined typologically as a result of architectural and functional analysis. It is indexed alphabetically (e.g., AK).

A book is the component of the archive which corresponds to a unit or an area.

Following is an example

of how the terms apply to a specific case at Mozan (see below, Figs. 14.3-5 for

a site plan that identifies on the ground some of the labels):

|

A |

a zone identified as a distinctive hill top |

|

A6 |

a unit and corresponding book identified logistically (sectors may be used, without a separate label, e.g., to distinguish an upper and a lower operation within the same unit |

|

AK |

an

area and corresponding book identified typologically (thus AK is the service

wing of the |

|

A6k1 |

a locus of a predefined size, i.e., a square; it is indexed with a single or double digit number |

|

A6k100 |

a locus within the unit/book; it is indexed with a triple digit number (without any particular relationship, in terms of labeling, to any square) |

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

(2) Analogical Representation of Elements

Digital is the term used for a file that provides a cluster of relays, sorted typologically, and given in numerical form. For example, such a file may contain the relays that define a wall; they are entered in a certain format (see below, …), which produces a script file, used in turn by such programs as AutoCAD to provide a graphic rendering of the wall.

A plot is a cluster of digital files, reproduced graphically on screen or paper.

A template is a graphic overlay on a view, identifying elements and referents, including especially secondary views; it can be drawn physically on a print or a drawing, or entered as layer on a digital photograph or drawing; see below, …). A template might be conceived as a primitive application of a GIS concept, applicable as long as the implementation of a GIS system remains technically and financially out of reach for an archaeological project.

A web is a cluster of views, taken at the same time and pertaining to the same cluster of constituents, each view being taken from a different angle; all views are interlaced together on the same template.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

(3) Typological and/or chronological sorting of elements

An assemblage is a cluster of elements, defined on the basis of typological analysis, e.g., walls or spouted jars. (See above, 13,4, for a definition of aggregate.) An assemblage may also be used to refer to elements of an aggregate that are presented not as found in the ground, but according to their typological specificity, e.g., the organized arrangement of the objects found in a burial.

A stratum is a minimal unit of reference relating spatial elements in terms of a temporal sequence.

A phase is an intermediate unit of reference relating spatial elements in terms of temporal sequence, and an horizon is a maximal unit of reference relating spatial elements in terms of temporal sequence.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents

13.7 Summary

Following are two lists of constituents,

the first sorted by type, and the second alphabetically by code. A full

synopsis is given in Fig. 13-2.

|

elements feature f item –

individual i components

of a lot qi, qp, qb para-elements composite c negative n trace e zero z q-lot q element cluster aggregate a assemblage b join j referent marker m relay r stratum s phase h view v drawing

(2D and 3D) w,y referent cluster locus k graphic g |

a aggregate b assemblage c composite e trace f feature g graphic h phase i item

– individual j join k locus m marker n negative p plot p plot q q-lot qb,qi,qp components

of a lot r relay s stratum t template t template v view w,y drawing

(2D and 3D) z zero |

Fig. 13-2 Synopsis of minimal constituents.

Note: We use the plural “loci” as in the Latin form.

Back to top: PART ONE: Nature and Structure of Constituents