Syria

The Syrian team included a group young students-14 years old- from Qamishli city, located in North-Eastern Syria, and is 25 KM to the west of Tell Mozan. The group of eight students was divided into two groups in order to have enough space of dialogue with the participants during the meetings. Most of the meetings were held in English to improve the linguistic level of the participants which is a key factor in the One-on-One meetings.

Our previous experiences and working in Syria have taught us how tricky it is to teach about archaeology and ancient past. For many reasons, that we won't mention here, the relationship between Syrians and the archaeological patrimony is missing to some extent. We were aware that the approach we follow will be decisive in the success or failure of the project. Therefore, we paid a lot of attention to not transform this experience to a history lesson. It was crucial to keep the students interactive with the archaeological information and help them develop their knowledge through their own curiosity and questions. Therefore, we started the formation officially as follows:

'Once upon a time there were a strong city called Urkesh, ruled by a king called Tupkish and his beautiful queen Uqnitum..'. The ancient city is 25 km to the west of your own city, imagine how was the life in ancient Urkesh and ask us-the archaeologists- your questions and curiosities to uncover its history, so we can write together the hi-story of Urkesh.

Here are some of the questions they asked:

- When did it start? Why did they build it here? When did it end and why? What religion did they follow? How many religions were there? How many ethnicities were there? Was it famous among other kingdoms? What resources did they have to make a strong kingdom?

- Did they write? Their language was ancient Arabic? How many tablets did archaeologists find?

- Did they live a war? Were they able to prosper after crisis?

- How did they leave the story of their life? How were you able to reconstruct their history? Was Tupkish a strong king and was he beloved by his people?

- How did the king communicate with his people? What relationship did they have? What was the communication system in general?

- How did you distinguish the Hurrian culture from other cultures? What ethnicity first inhabited it (before it was a Hurrian city)?

- Were they interested in Astronomy? Did they have an architectural style, different from other cities in the region? Did you find a cemetery for ancient Hurrians? How was it? When did Urkesh reach the peak of properness and why? What was the size of Urkesh?

- What was the name of the last king who ruled Urkesh?

Leaving their questions without answer was exciting for the students since they started to think of the answers by imagining themselves as charterers in ancient Urkesh, taking examples of some parallels in their modern life.

The questions gradually developed to have a logical line, so they can construct, through the answers, the history of ancient Urkesh. To some extent, it was like excavating the site again, with a faster pace.

At the end of the formation, students were invited to visit the site so they can 'live the history' being surrounded by the ancient monuments they learned about.

The visit was organized with our local archaeologist in the field, Amer Ahmad, who was ready to explain further any missing information. The visit was open to the participants, their families and friends.

|

|

|

During the visit many students took the initiative to explain certain features or monuments that they became fond of, to their relatives and friends. Others were inspired by the site and read a small poetry they wrote in front of the visiting group. While most of the students recorded the site through their pictures, some were interested in showing the site through a short report on their Instagram in Kurdish and English to invite other locals in the nearby cities to discover Urkesh.

The site visit concluded Phase-1 and students were encouraged to think of presenting what they consider relevant or interesting for them from the ancient site of Urkesh, using their own parlance, talents and creativity.

|

|

Italy

Due to COVID-19 most schools in Italy shifted to online learning. The new method of learning, and lack of previous organization, left most students and their teachers exhausted from the online experience. Therefore, phase-1 with the Italian group was completely different from the Syrian one. We didn't seek any type of formation regarding the cultural patrimony. We focused instead first, on discussing the favourite features of the youngsters regarding their cultural patrimony, what is relevant to them and what parts they would communicate to the rest of the world as a representative of their identity. The second aspect we focused at was their ability of communication in English. Since the participants showed difficulties in communicating in English, we offered them an English support to improve their linguistic level and to be able to communicate with their peers in English.

Based on the common interest between the Italian participants, they chose the San Carlo Theatre in Naples to present to their peers in Syria. As it's commonly agreed, the theatre is an important monument to the city and the whole nation. However, the participants elaborated critically the reasons behind considering this monument is interesting for the young generation. This process helped them to choose the valuable aspects of the theatre's life. The challenging part for the Italian participants was how to show really the important role of the theatre to their peers in Syria, where theatre doesn't make part of the common popular culture.

These challenges pushed the participants to take a step back of the common discourses regarding the value of the monuments and to think creatively in how to interpret their own culture and interest to others. It led them to deepen their knowledge of their own patrimony while trying to communicate it to others.

Greece: Corinth Excavation

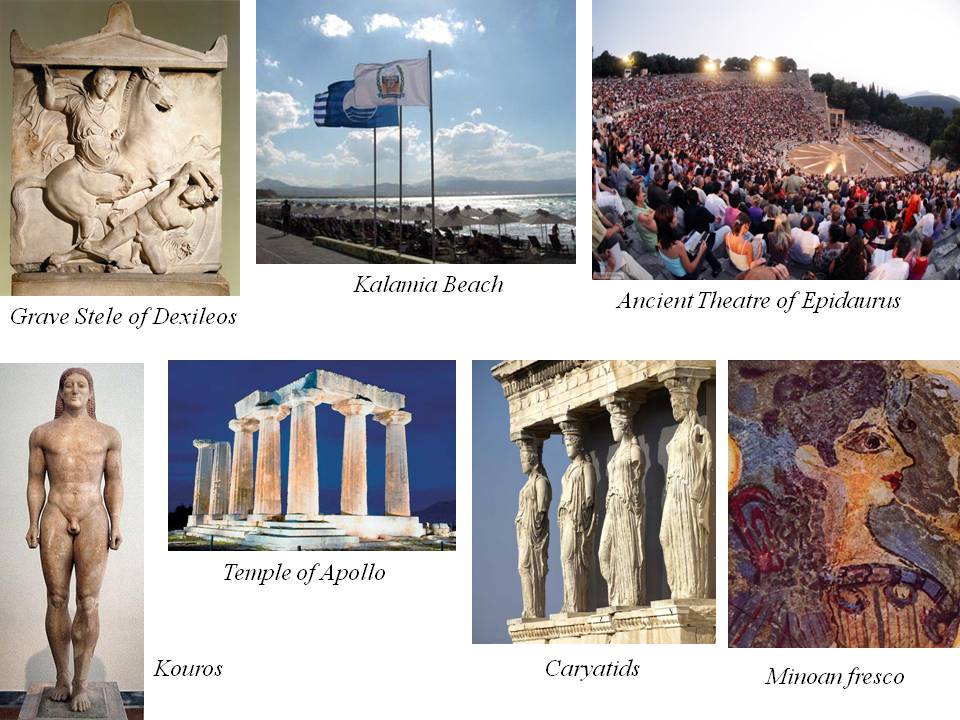

Prior to phase-2, students were asked to prepare short assignments in English that includes three photographs and to write brief descriptions of each. The assignment included: one image of an archaeological artefact or monument from Ancient Corinth, one image from any archaeological site or museum in Greece, and an image of their favourite place in Corinth. Some students chose the Temple of Apollo as the emblematic monument of Ancient Corinth, others chose caryatids and kouroi as examples of famous statues from ancient Greece, and most students chose Kalamia Beach, the central beach of Corinth, as their favourite place in Corinth.

Prior to phase-2, students were asked to prepare short assignments in English that includes three photographs and to write brief descriptions of each. The assignment included: one image of an archaeological artefact or monument from Ancient Corinth, one image from any archaeological site or museum in Greece, and an image of their favourite place in Corinth. Some students chose the Temple of Apollo as the emblematic monument of Ancient Corinth, others chose caryatids and kouroi as examples of famous statues from ancient Greece, and most students chose Kalamia Beach, the central beach of Corinth, as their favourite place in Corinth.

Similar to the Italian participants, the Corinth group was challenged to think how to reveal the value of their heritage to the Syrian peers who are not familiar with the Greek ancient history.

Back to top