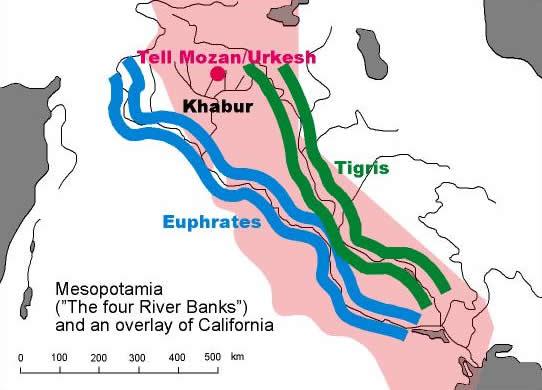

Tell Mozan is the site of the ancient city of Urkesh - which was known from myth and history, and which our excavations have firmly placed at this location in northeastern Syria. Its beginnings are as yet unknown, but they date back to the at least the early part of the fourth millennium B.C. It was a main center of the Hurrians, who celebrated it in their myths as the home of the father of the gods, Kumarbi. It was also the capital of a kingdom that controlled the highlands immediately to the north, where the supplies of copper were located that made the city wealthy.

What appears now as a natural hill is but a city shrouded within its own collapse - fragments of distant moments in time unpredictably layered and intersecting in the spatial bundle of buildings and strata. Through our work at this archaeological site, the hidden connections among these fragments are yielding, at Mozan, a coherent picture of the once cohesive urban landscape of Urkesh.