Hurrians

|

The Hurrians were a small, but very influential, population of the ancient Near East. Until our excavations, they were known primarily from the second millennium (most scholars assumed that that was when they first came into the region). The discovery of Urkesh has now pushed back the earliest evidence for the Hurrians well into the third millennium. This is no small feat: Urkesh is not just another city along the many we know from Syro-Mesopotamia; it is a window into a new civilization, in many ways alternative to that of the Sumerians, the Akkadians and the Amorites. The most distinctive trait is their language, which is wholly unique, unrelated to any other known ancient or living language. We do not have many Hurrian texts as yet from Urkesh, but they are the earliest known. Also very distinctive is their religion. Their myths were preserved in later periods by the Hittites, and they are reflect a mountain environment, with particular reference to volcanic phenomena that are, understandably, unknown in the southern mythologies. Urkesh plays a central role in these myths as the seat of the ancestral god of the Hurrian pantheon, Kumarbi. Even more important is the cult. The ābi (cf. unit A12) is a wholly unique structure that gives evidence of necromantic rituals in clear contrast with the religious mentality of the Sumerians and the Akkadians. Thus it is not just that the Hurrians had deities with different names: rather, they had developed quite an alternative conception of the divine world and of the means through which humans can get in touch with it. Politically, it is significant that the rulers of Urkesh used a Hurrian royal title not otherwise known for any other Syro-Mesopotamian kingdom - endan. This amounted to an explicit affirmation of ethnic identity and political self-assertion, all the more significant since at that very moment the Akkadian empire was expanding throughout Syro-Mesopotamia. And the only third millennium Hurrian text known so far, the inscription of Tish-atal, is a political text recording the building of a temple in Urkesh. As of now, no other archaeological site can claim the same type of evidence for Hurrian identity as we have for Urkesh. To some extent, this is because there were probably only few properly Hurrian cities, distributed along the piedmont arc of what is now northern Syria - which we have called the Hurrian urban ledge. This points to the centrality of Syria in the history of civilization. It is more appropriate to think of it as a pivot, rather than a crossroad (as is often said), of civilizations. One does not go through Syria to get somewhere else. Rather, fundamental new patterns of political organization and ideological conceptualization originate here. And excavations like those of ancient Urkesh are the only way in which we can understand this fundamental role of Ayria in world history. Back to top |

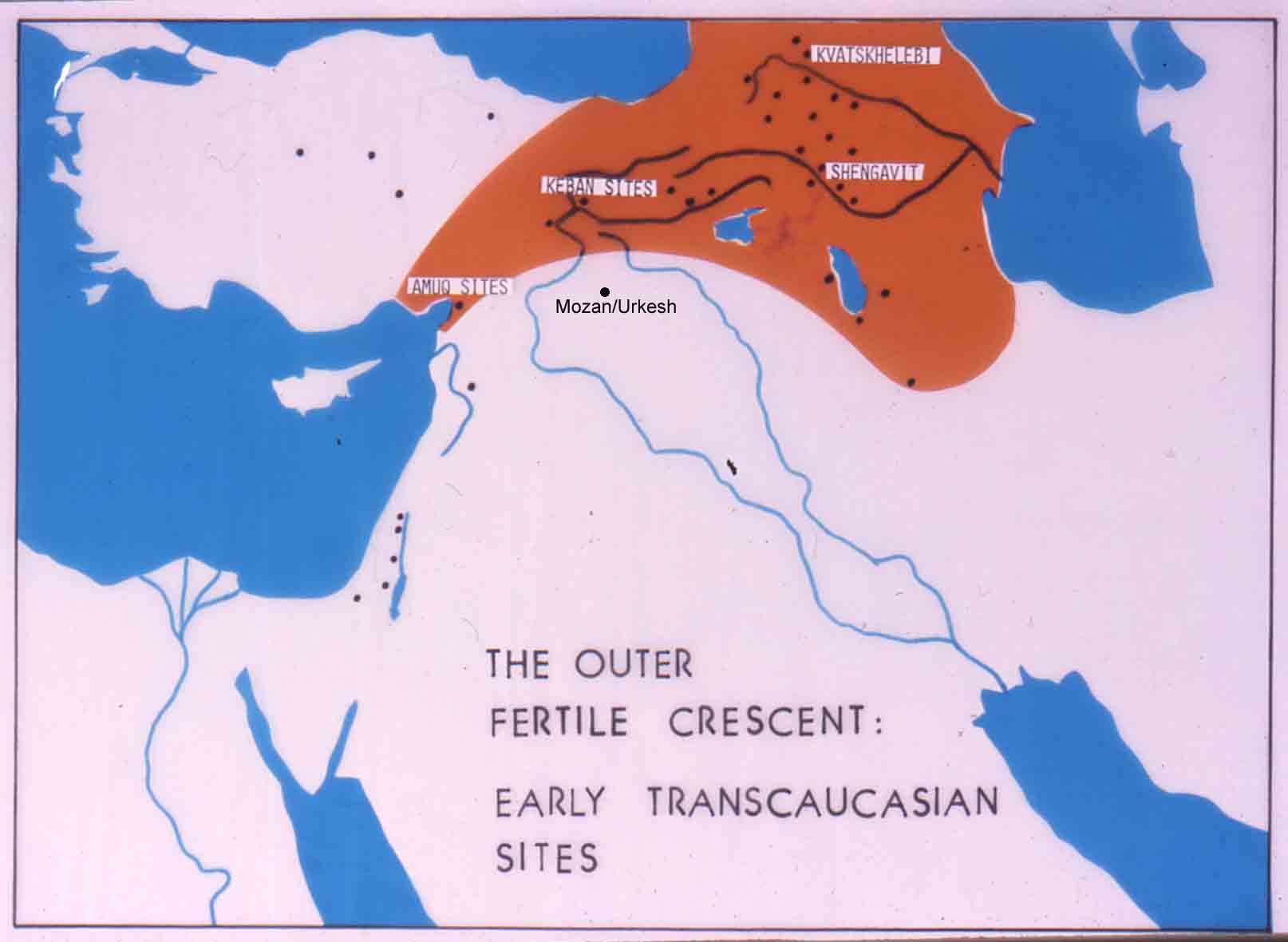

The "Outer Fertile Crescent"The populations of the northern highlands shared many traits of material culture and of ideology. We refer to this region as the Outer Fertile Crescent, because it overarches the region traditionally known as Fertile Crescent.In the third millennium, they are known as Early Trans-Caucasian in terms of the archeological record. We now think that there was an ethnic bond that united these populations. From later evidence, we think that they identified themselves as Hurrians. Back to top |

|

Ideological landscapes

It is a curious phenomenon that the myths and epics of southern Mesopotamia (Sumerian and Akkadian) show a sharp and diffused awareness of the extra-Mesopotamian landscapes to the east, the south and the west, but not to the north – which is wholly absent. |

|

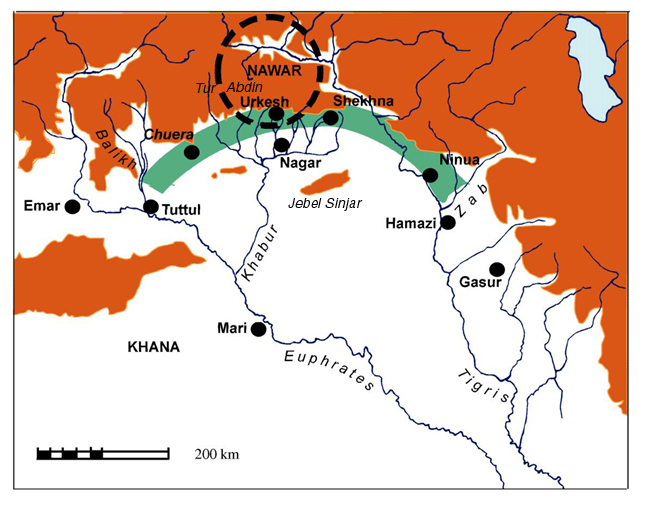

The Hurrian "urban ledge"While important and autonomous, the Hurrian urban culture was not represented by a large number of cities. Only a small number can be so considered, and they seem to have been found only along the narrow strip along the piedmont of the Taurus range (shown in green on the map). As of now, Urkesh is the only city that can demonstrably be shown to have been Hurrian in the third millennium.Nawar was (arguably) the name of the territory of the kingdom of Urkesh, that included the mountainous hinterland to the north. There is no evidence that Urkesh ever developed into anything larger than a city-state, however extensive its hinterland and powerful its culture. Back to top |

|

At the boundary of the empireThe Akkadian expansion threatened to engulf Urkesh as the empire established military and administrative control a few kilometers south of Urkesh, at ancient Nagar. But there is no evidence that Urkesh was conquered. Rather is seems (arguably) that the daughter of the most powerful Akkadian king, Naram-Sin, was married to the king of Urkesh.Such dynastic alliance was probably influenced by the fact that normal Akkadian administrative controls could not easily be imposed on the mountainous hinterland: as a result, an alliance seemed more realistic than a conquest of the capital city, Urkesh – however easy such a conquest might have been, in military terms. Back to top |

|

A vassal kingdomIn the early second millennium, Hurrian influence is still visible in the material culture, but political control passes in the hands of the Amorite kings of Mari. They had established a large macro-regional state in the north, and installed their own man in Urkesh, with an Amorite name, as their vassal king.The local inhabitants did not take kindly to this intrusion, and letters found at Mari give evidence of their strong resistance. In one letter, the king writes to his vassal the man of Urkesh as follows: "I did not know that the sons of your city hate you on my account. But you are mine, even if the city of Urkesh is not." Back to top |

|

BibliographyFor a bibliography about the Hurrians, see here; for a specific bibliography about "Urkesh and the Hurrians", you can visit this page.Back to top |