Back to top: The laboratory

The process

The system, as it is organized in Mozan, is such that all the objects that are excavated from each unit are described and measured in the incoming objects area and eventually, if needed, drawn and photographed. Each unit has one person in charge of this task. There is a distinction between the “items” [i], objects that are triangulated because their precise location is of importance, and the “q-item,” pieces that are coming from a specific volume of excavated soil which is precisely measured in terms of elevation and horizontal location. These are usually the more common finds, such as lithic artifacts, or pieces that are less identifiable because they are fragmentary. Of course the decision on whether measure the spot of a find depends on the common sense and experience of the excavator: a potential sealing impression or a piece of metal that seems whole is always triangulated if possible, while the very common flint blades or a bit of corroded metal can be collected as a q-items.

Very often the pieces that have been unearthed are hard to “read,” due to the amount of incrusted soil around them, and often, if they are made of unbaked clay, they are still damp and must dry before they are touched. After the person in charge of the objects has slightly cleaned the object with soft brushes and is able to understand which type of object is being analyzed, the final destination of the piece is decided, according to a few main categories that correspond to areas of specialization, the typological units: the ceramic objects are handed to the “pottery” staff who wash them and analyze them, the whole process is supervised by M. Kelly-Buccellati; seals, seal impressions (= sealings) and important objects are also handed to M. Kelly-Buccellati; epigraphic material goes to G. Buccellati; the animal figurines and wheels go to R. Hauser, the metals go in the conservation laboratory for treatment, inventory and storage. If in any given season there is, for instance, an expert on reeds and basket impression, all clay pieces bearing such impression would be handed to that person. All the other minor categories of objects, such as beads, shells, bone and lithic artifacts, are stored in boxes divided by materials, all kept together in the collections storeroom.

There are two ways from which objects arrive to conservation:

- After the objects from each unit have been processed, a decision is taken as to which objects are to be directly stored for later analysis, which objects are to be stored based on typology, or those that go to the typological specialists. At this point, the typological specialists may decide to send an object to conservation. Of course, to make thing easier, for some routine procedures like the ceramic vessels restoration, the step from the digging unit to the typological unit, in this case M. Kelly-Buccellati, is skipped and the vessel's sherds are taken directly to conservation: there would be no point for the specialist to see a pile of sherds when the same reconstructed shape can be studied after conservation.

- All metals finds go straight to the conservation laboratory, regardless of their condition, to be treated and eventually stored.

Back to top: The laboratory

The staff

The conservation team can vary from year to year. In recent years, the metal finds have been treated by Beatrice Angeli, a conservator from the Opificio delle Pietre Dure (OPD, in Florence), and the ceramic material is treated by one or two local people from the nearby village of Mozan under the supervision of the writer. To provide an example of how the conservation activities could be organized, one can look at the 2001 campaign, which has been particularly productive in terms of conservation. First of all, quite a number of people were involved: there were 5 persons to treat the metals, one for the pottery, and the writer for the rest of the objects and for recording data. Beatrice Angeli has been coming to Mozan since 1999, and after an institutional agreement was reached between the IIMAS and the OPD in the fall of that year, she has been able to bring along four students in their second year of the OPD bronze restoration program. The five of them worked on a large amount of metal pieces from the previous seasons and from the current season, selecting the most significant objects in order to send them to the Deir-ez Zor museum. Most of the pieces were photographed before and after the treatment, and were drawn by the conservators themselves.

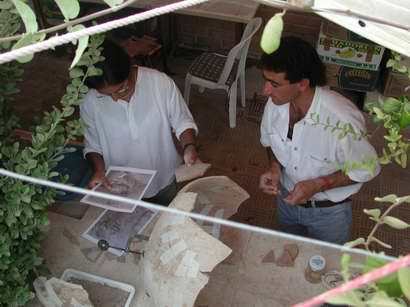

Beatrice Angeli has been coming to Mozan since 1999, and after an institutional agreement was reached between the IIMAS and the OPD in the fall of that year, she has been able to bring along four students in their second year of the OPD bronze restoration program. The five of them worked on a large amount of metal pieces from the previous seasons and from the current season, selecting the most significant objects in order to send them to the Deir-ez Zor museum. Most of the pieces were photographed before and after the treatment, and were drawn by the conservators themselves.In keeping with the shared objectives of the Mozan project and the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, the students during this, their first experience in the field, took part in various aspects of the work in the excavation, especially with regard to the excavation of metal artifacts. Some of them have also been actively digging, and others have drawn several burials. Their involvment in the excavation itself was one of the most meaningful aspects of the collaboration between IIMAS and OPD.  The restoration of pottery was mainly carried out by Steff Mustafa, who has been doing that under the writer's supervision for the last 4 years. All the other artifacts such as unbaked clay figurines, seal impressions, stamp seals, were treated by the writer.

The restoration of pottery was mainly carried out by Steff Mustafa, who has been doing that under the writer's supervision for the last 4 years. All the other artifacts such as unbaked clay figurines, seal impressions, stamp seals, were treated by the writer.The converse of conservators becoming familiar with archaeology is that archaeologists must develop sensitivity and skills in conservation. Accordingly, a number of the students who serve as staff members are engaged in the work of the laboratory, under the direct supervision of the writer. |

Back to top: The laboratory

The facilities

| The conservation facilities are considerably well organized in terms of space and equipment. Initially, in 1997, there was only one large room; in the following years, little by little, additional spaces have been gained. First came a little veranda, that was attached to the lab, which has been closed with windows and provided with an air conditioning system. This room has plenty of natural light and can be used to work on large pieces that cannot be worked on in the main room. Another room, the one before the main room, which was at first used for the natural sciences (now moved to a different set of rooms), has also been devoted to conservation, to house additional staff when necessary, for example the 4 student of the Opificio who came in 2001. |

|

|

|

|

first room looking towards second room |

second room looking towards first room |

second room looking towards veranda |

|

|

|

| veranda looking east | veranda looking west |

Back to top: The laboratory

Recording system

All the objects that pass through the conservation lab, either for permanent storage, as the metals, or for specific treatment, are recorded in the conservation register in very practical and useful manner that has been set up and improved over the last 3 years. The same data recorded on specific conservation forms are also entered in the computer with a system that allows each unit to have access to the information regarding their objects.

The description includes a brief functional note (e.g., “arrowhead”), and details about the material they are made of, their shape and condition (e.g., “long thin arrowhead broken in 3 parts, the metal is very corroded”). The treatment is then specified, for instance “cleaned, glued,” followed by notes of various kinds that are usually about the treatment, for example “finish the treatment next season.” In this category of notes it is also mentioned who phisically performed the treatment.

Back to top: The laboratory

Types of material: ceramics

|

We consider here the threee kinds of material most commonly treated in the conservation laboratory, in descending order: ceramic, metals, unbaked clay artifacts.

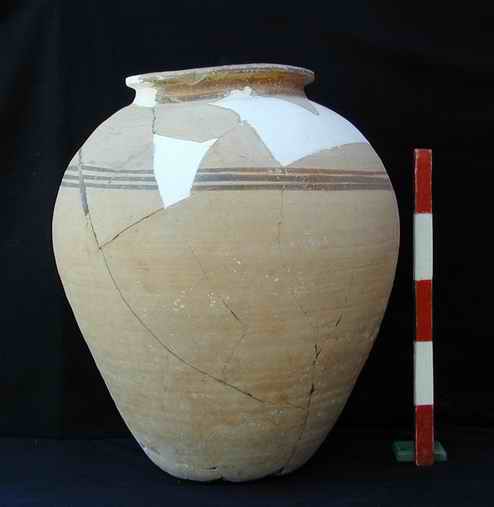

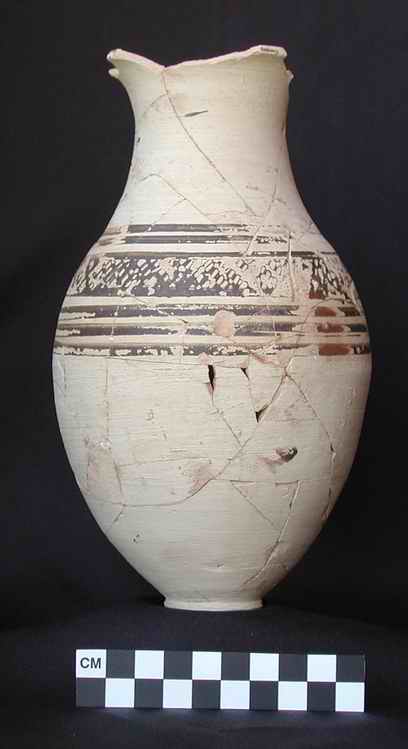

The majority of the material is undoubtedly those made of ceramic. It must be considered that 99% of the sherds that are excavated are processed for the purpose of ceramic statistics and don't need any conservation; the ceramic material that needs treatment is mainly composed of vessels that are found broken in the ground but almost complete and thus can be reconstructed. If a vessel turns out to be missing too many pieces to be reconstructed, an attempt is made to reconstruct at least the profile in order to draw the section.  If found in graves, the ceramic vessels are usually whole; if found in private houses they are often fragmentary, sometimes they are found fractured but still with their original shape because of the dirt. When a pot smash is found, where it is unclear at a first sight if the shape could be reconstructed or not, the only thing to do is to try to reconstruct it, by looking first at how much of the base and of the rim are present. If there is enough surface, the reconstruction is attempted and the gaps left by missing sherds are reconstructed in plaster. If there is not enough material, as it turned out to be the case of a cooking pot (A16.30, shown here as it was found in the ground), there is no point in trying to reconstruct it. All of the whole or reconstructed vessels are subsequently drawn and photographed.

If found in graves, the ceramic vessels are usually whole; if found in private houses they are often fragmentary, sometimes they are found fractured but still with their original shape because of the dirt. When a pot smash is found, where it is unclear at a first sight if the shape could be reconstructed or not, the only thing to do is to try to reconstruct it, by looking first at how much of the base and of the rim are present. If there is enough surface, the reconstruction is attempted and the gaps left by missing sherds are reconstructed in plaster. If there is not enough material, as it turned out to be the case of a cooking pot (A16.30, shown here as it was found in the ground), there is no point in trying to reconstruct it. All of the whole or reconstructed vessels are subsequently drawn and photographed.

To give an example of the ratio of restorable ceramic vessels in an average excavation unit, of the 40 miscellaneous pieces of the A16 conservation list for 2001, 6 are ceramic vessels that have been reconstructed, namely 4 jars (of which A16.2 and A16.9 are shown here) and 2 bowls (of which A16.58 is shown here), of various sizes. Besides these reconstructible shapes (plus A16.71 which is only half a jar along the vertical section), there were 2 more vessels that came out intact from the ground, a small jar (A16.14) and a carinated bowl (A16.45), and there may be another 4 pieces coming from the 3 graves excavated at the end of the excavation season(A16.61, 62, 63, 64) the material of which still needs to be processed.

To give an example of the ratio of restorable ceramic vessels in an average excavation unit, of the 40 miscellaneous pieces of the A16 conservation list for 2001, 6 are ceramic vessels that have been reconstructed, namely 4 jars (of which A16.2 and A16.9 are shown here) and 2 bowls (of which A16.58 is shown here), of various sizes. Besides these reconstructible shapes (plus A16.71 which is only half a jar along the vertical section), there were 2 more vessels that came out intact from the ground, a small jar (A16.14) and a carinated bowl (A16.45), and there may be another 4 pieces coming from the 3 graves excavated at the end of the excavation season(A16.61, 62, 63, 64) the material of which still needs to be processed.

|

Back to top: The laboratory

Types of material: metal objects

The second main category of finds that come to conservation is represented by the metal objects. This a particular case because, as already mentioned, it has been decided that, regardless of their condition, the laboratory would be the ideal place to store them given their usually fragile preservation. Accordingly, all metal finds are taken to the conservation laboratory directly from the excavation, after their label is recorded in the objects book. Not all of them need a treatment: certainly they all need to be cleaned from the soil around them which in same cases can be very thick and hard, in others merely a light coat of dust; this is done when the soil is dry.

Usually about one third of the metal finds are whole pieces, and two thirds are broken pieces or fragments. Naturally, the state of preservation of the metal surface can vary a great deal, from good condition (which rarely occurs) to very damaged by corrosion products, where only the core is still good (the majority of cases) and to mineralized metal where the metal has lost all his chemical features and has totally turned into corrosion salts (rare). The decision as to whether or not the conservator should treat a piece depends on its importance, based on its function, typology and stratigraphy, and also on its state of preservation both in terms of shape and of the metal itself: the choice between a whole spearhead and a damaged bit of pin is obvious.

The way the metals are stored depends on their typology: in the first 10 years of excavations all finds were stored together in boxes regardless of the material they were made of, and the boxes were divided by year. In 1998 a first attempt was made to reorganize and collect all metal finds from the previous seasons and they were all stored in the conservation laboratory in separate boxes according to their typology.

Basically the finds are composed of three main categories: weapons, such as speareads, arroweads, javelins; functional objects like pins and various kinds of tools; body ornaments such as earrings, bracelets, necklaces. In 2001 an additional improvment was carried out with regard to the classification and inventory system, as a part of the general new registration system that includes all type of objects; now the numbering of the boxes for the metals storage, although they are not physically kept together with all other materials, follow the same pattern used for the other types of objects.

Back to top: The laboratory

Types of material: clay objects

The last class of finds that are taken to conservation is that of the clay objects other than ceramic vessels, whether baked or not, and they can be further divided into figurines (usually animal but also human), seal impressions and tablets, wheels and miscellaneous objects. These pieces are often damp when they come out from the ground, and if not secondarely fired they can be extremely fragile. They usually need to be cleaned, consolidated and glued. While the animal figurines, normally baked, can easily by cleaned of the excess dirt by the person responsible for the objects, and thus are not often taken to conservation, this is usually not the case with the much more delicate sealimpressions that in 90% of the cases are taken to conservation, where they are left to dry and then are cleaned. Depending on the quality of the clay and on its hardness, they can be very hard and easy to clean, or extremely crumbly and difficult. To clean these, a magnifiyng lens and in some cases a microscope are usually necessary, together with scalpels, dental tools and needles.

It must be considered that, even if never mentioned in the conservation register, there are many other types of finds, basically all the lithic artifacts such as stone beads, flints and cherts, wheights, mortars and pestles, that are found in large quantity.

Back to top: The laboratory

Bibliography

About conservation refer mostly to:

- Agnew, Bridgland 2006

- Agnew, Demas 2004

- Agnew, Demas 2019

- Bonetti, Buccellati G. 2003

- Buccellati, Kelly-Buccellati 2017

- Buccellati, G. 2000a

- Buccellati, G. 2006a

- Buccellati, G. 2019b

- Stanley Price 1995

- Viscuso et al. 2018

Cf. also the dedicated bibliographical page.

NOTE: on this topic, cf. also the dedicated topical book on “CONSERVATION”.

Back to top: The laboratory