Back to top: Digital thought 2. Non-contiguity/capillarity

The concept

It is in the nature of creative thought to link phenomena or ideas that do not in and of themselves appear to be connected. We can project such a process behind some of the earliest creative enterprises that can be attributed to the ingenuity of human beings. To start a fire at will entailed seeing the potential of friction when applied to inert materials such as stones or wood. A trap entailed the connection between a triggerable mechanism and the potential animal that would set it off. The placing of a seed in the ground at one point in time entailed the expectation that a plant would grow at a much later point in time. None of the elements that make the connection real are contiguous in space or time – not the stones and the resulting fire, not the trigger and the animal to be trapped, not the seed and the plant that germinates from it.

Obviously such examples, rooted as they are in a remote past, show that how to bridge the gap between non-contiguous elements is by no means the exclusive of a digital mode of thinking. We have to see, therefore, what if anything is so new in digital thought that makes the bridging of non-contiguity qualitatively different from its antecedents.

Back to top: Digital thought 2. Non-contiguity/capillarity

The dislocation of the natural sequence

It is instructive to view the advent of digital thought against the background of twentieth century art, music and literature. Common to all is the search for a re-configuration of the natural sequence, one that dislocates the contiguity of elements and reshapes them into a new whole – whether in painting with, say, cubism, or in music with atonality, or in literature with the staccato rendering of a stream of consciousness.

We are witnessing here the converse, it would seem, of what creative thought attempts to do. Where the latter seeks to bridge the seeming disconnect, the former seeks to dismember an existing connected whole. This is generally viewed as an escape from naturalism. But one may consider an alternative understanding. In both naturalism and “abstract” art the underlying presupposition is that the creative person and the recipient of the creation share a common communicative code. The recipient (viewer, listener, reader) assumes certain limits within which the creator operates and the recipient receives. In “naturalism” the shared expectation is defined by the natural sequence, and it is those limits that define the compositional structure of the resulting whole. In the “abstract” version, the limits of expectation are changed: it is now the dislocation, rather than the coherence, of the natural sequence that defines the limits. But the communicative process remains the same: establishing limits within which communication is understood.

The very acceptance of dislocation is of interest to us here – because it suggests a new focus on the fragments seen in themselves and on the ability of the human creative effort to recompose them in a different unity.

Back to top: Digital thought 2. Non-contiguity/capillarity

Bridging the dislocation

Against the background of this new sensitivity we can better understand the development of digital thought with regard to non-contiguity. We are trained to accept more readily the potential contiguity, as it were, of elements which are not in fact contiguous. We are undaunted in front of fragmentation, because it is by now our second nature to assume secret kinships (a term dear to semiotics, with a different meaning) among floating particles, whether or not we can detect the bonds that ground the kinships. We have developed an instinctive faith in the unbounded potential for reconstitution into unity of the most disparate elementary particles. And thus we relish the fragments, attracted as we are by the hidden dynamics they seem to display eve when we do not know the target towards which that dynamism tends.

In a digital way of reasoning, this means that we accept, more readily than ever before, vast masses of non-contiguous elements, expecting the hidden connectivity to emerge as we tickle the individual pieces. Thus it is that we come to feel instinctively that the dislocation is there to be bridged, that even the most amorphous data-mass is in fact potentially a database, subject to an articulation that reveals the polarities and the resulting unity.

Back to top: Digital thought 2. Non-contiguity/capillarity

A hierarchy of nodes

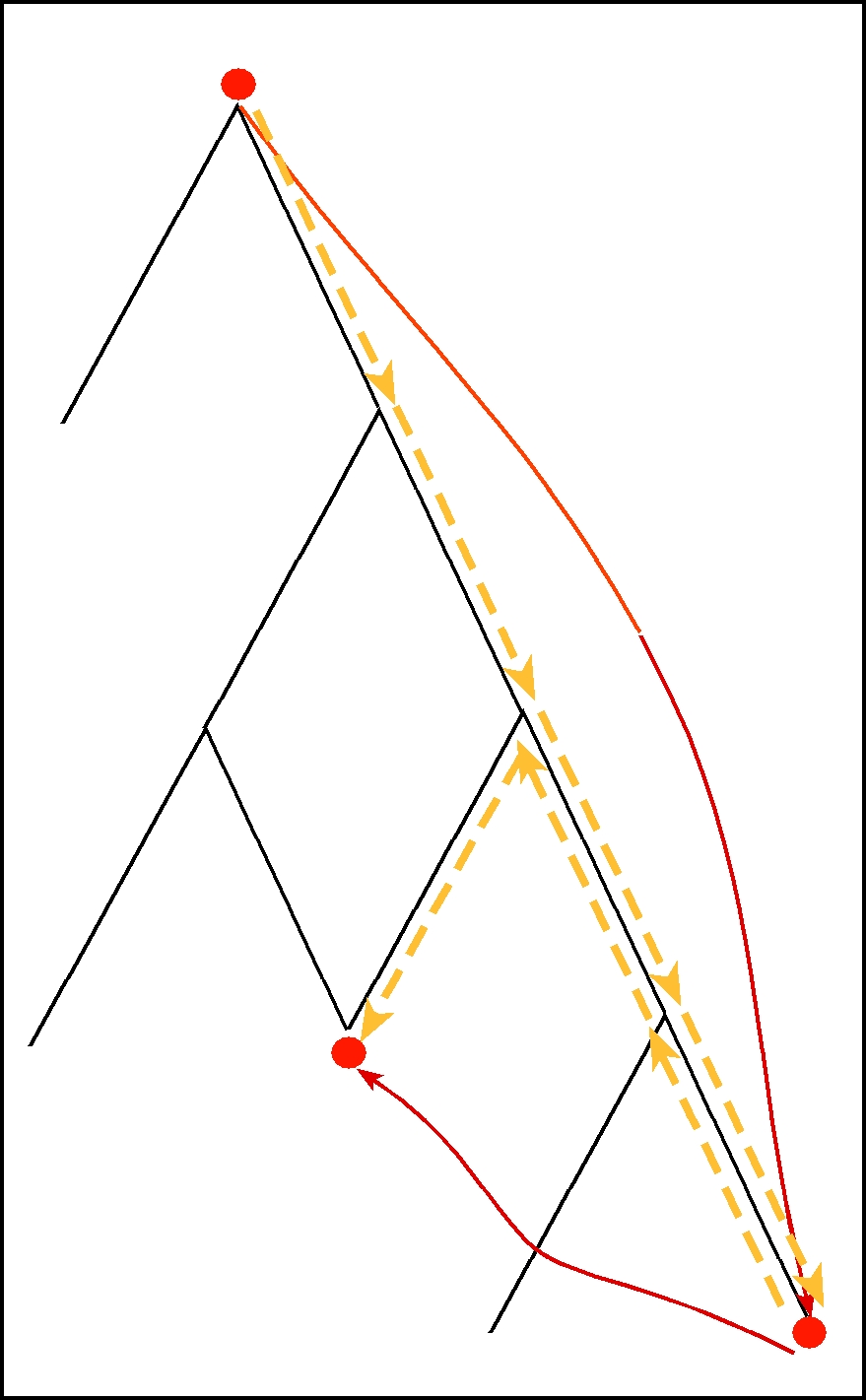

What digital thought introduces explicitly is a framework of nodes that subsume the fragments. The nodes are in a hierarchical relationship to each other, with a variety of intersecting hierarchies. Thus while the fragments retain their autonomous status, their inherent capability of being reassembled (*) gives them a wholly new power. Connectivity is raised to a much higher power because of the unlimited potential for the interlacing of hierarchies and of the elements they subsume.

The archaeological process is a perfect paradigm, as this whole website, and in particular the Urkesh Global Record (UGR), seek to illustrate. The enormous quantity of data, however minute, can be accessed within a framework of nested hierarchies that allows the bridging of non-contiguity at a multiplicity of different levels.

Back to top: Digital thought 2. Non-contiguity/capillarity

Capillarity

|

This bridging may be defined as capillarity. We can reach instantly from the highest nodes (say, the broad issue of chronology seen on the macro-scale of centuries) to the most minute piece of evidence (say, a single sherd – a specific case that is presented in detail separately). It is through their dependence on the higher nodes that the fragments find their congruence. And because of the chain of nodes, each terminal point is potentially linked to any other one within the tree, in such a way that linkages can instantly be established without explicitly transiting through the intermediate nodes, but through leaps darting across the tree (shown in red), supported by the underlying web of filaments across which the logic of the trajectory flows (in dotted yellow). |

|

Back to top: Digital thought 2. Non-contiguity/capillarity

Notes

(*) The classical formulation may be found in the description that Socrates gives of himself in Plato’s Phaedrus as “the lover of fragmenting and re-assembling” (erastés … tôn diairéseon kaì sunagogôn, Phdr. 266b). Back to text

Back to top: Digital thought 2. Non-contiguity/capillarity