Back to top: Sequentiality: meaning vs. control

Argument flow

argument based and ad hoc

We must distinguish between the logic of an argument and the form in which it is presented. If we use the terms “linear” to refer to the modality of the argument, we may use the term “sequential” to refer to its substance. We may thus say that the argument will always be sequential, regardless of whether the form it takes is linear or not.

In the schematic rendering below, the intermediate steps a-b-c-d must be in that sequence for the argument to hold. In this representation, these intermediate steps are all on the same plane, which results in an aligned set of arrows. But the steps may straddle across planes, resulting in a multi-linear or multi-layered arrangement – where sequentiality remains nevertheless the rule.

Schematic representation of sequentiality within argument

Back to top: Sequentiality: meaning vs. control

Meaning vs. control

Sequentiality proper aims to seek for a meaning as yet unknown

Current use of website aims to seek control of the already known

Back to top: Sequentiality: meaning vs. control

The polyhedral argument

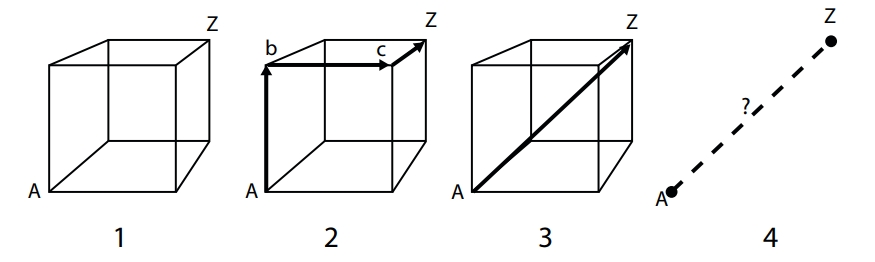

The adjective “linear” refers to the geometric figure of a line, i. e., a point moving along a fixed direction. The adjective “polyhedral” refers to the geometric figure of a solid bounded by polygons, such as the cube represented as 1 in the figure below. A linear argument that proposes to link conceptually points A and Z has to travel along points c and d (2 in the figure). A polyhedral argument, on the other hand, travels directly, across the solid, from A to Z (3 in the figure).

The power and demonstrability of a polyhedral argument relies on a prior knowledge of the cube and of its properties. It is only in virtue of this knowledge that A can arguably be linked with Z, since the whole structure of the cube is presupposed, hence the linear possibility of the link (as represented under 2) is virtually known, even if it is not followed. It is also as a result of the prior knowledge of the underlying structure (represented figuratively as a polyhedron) that the linkage takes place along the shortest line (as represented under 3).

Hence the power: it is the knowledge of the whole that allows the linkage. And hence the demonstrability: one can refer back to the nature of the solid and show how the link between the two is possible. Such a knowledge is “polyhedral” because it does not rely solely on points c and d, but rather on the whole solid figure (the cube or polyhedron), of which c and d are as much part as A and Z.

Without a knowledge of the whole, i. e., without a supporting structure such as the cube, points A and B are floating in space, and their linkage (as shown schematically under 4) results from a hit or miss shot in the dark.

Schematic representation of linear vs. polyhedral arguments

(from Backdirt 2007, p. 37)

Back to top: Sequentiality: meaning vs. control